They promise to boost your energy. They promise to boost your strength. They promise to boost your focus and mental clarity. They even promise to boost your looks. It seems like there's nothing a vitamin or supplement bought on the Internet can't help improve these days.

Estimated to be worth about $37 billion as of 2017, the vitamins and supplements industry in the U.S. has seen a steady rise since the turn of the millennium. (While the FDA regulates and defines both vitamins and supplements as "dietary supplements," vitamins are generally agreed to be compounds naturally occurring in food, whereas supplements may be any combination thereof or mix of other elements like minerals, herbs or amino acids that are said to possess health benefits. For the purposes of this article, we may refer to the two interchangeably.)

There are many ways you could account for these growth trends (not the least of which is a look at aging populations), but it's no coincidence that there have been a number of eye-catching new vitamin and supplement brands entering the marketplace at the same time as there's been an explosion in our cultural consciousness of things like wellness, self-care, organic eating, detoxing, all-natural products and more.

A survey of some of the more high-profile new brands out there shows the breadth of choices consumers have. You'll encounter brands like Ritual or Care/of whose clean packaging wouldn't feel out of place in a medicine cabinet alongside a bottle of Glossier's milky jelly cleanser or on a nightstand next to your Casper mattress; goop Wellness, a spin-off of Gwyneth Paltrow's goop blog, whose chic little protocol packets can nestle in the bottom of your Mansur Gavriel bucket bag; Moon Juice, whose cosmic DIY vibes, hand-drawn font and upmarket price points conjure lighting some $20 palo santo incense and making homemade all-natural face masks; Old School Labs, whose retro, Soviet propaganda posters-by-way-of Shepard Fairey-style packaging would complement that pair of Chuck Taylors you recently started wearing to lift weights at the gym; JYM, Onnit and Kion, whose sleek, utilitarian bottles can provide the pre-workout fuel needed before you begin a new regimen you heard about on a podcast by one of those brands' founders, Jim Stoppani, Joe Rogan and Ben Greenfield, respectively; InfoWars, whose in-your-face packaging and frenzied messaging would feel right at home on a shelf in that bunker you're building after hearing about the impending apocalypse from — who else? — far-right conspiracy peddler and the brand's founder, Alex Jones; and more.

Each of these brands, in their own way, promises not only health benefits but also the possibility of being part of a distinct lifestyle. That's why it can seem so jarring to learn that many of them sell the exact same things. As a 2017 article in the New York Times Magazine first pointed out, brands as disparate as Moon Juice and InfoWars both sell products containing ingredients like cordyceps, reishi mushrooms and maca, to name but a few. (Maybe this means that even if we can't agree on anything else in politics or the culture wars, we can come together over a love of difficult-to-pronounce adaptogens like ashwagandha). But, because many of these companies are producing the same — or very similar — products, the branding, marketing and storytelling of each one becomes that much more important.

There's a lot of freedom in marketing vitamins and supplements, reflective of the fact that there's less regulation when it comes to starting these types of companies compared to founding a pharmaceutical brand or inventing a new medication. That's because unlike the drug industry, the supplements world is one big, unregulated Wild West. Thanks to the Dietary Supplements Health and Education Act (DSHEA) of 1994, vitamins and supplements can avoid any clinical trials that would prove quality, efficacy or even safety.

Put another way, as long as companies are not actually harming consumers, they can put whatever they want in a bottle and effectively tell you whatever they want about it. If it seems murky that this sector of the health industry would be so unregulated — especially when countries like Canada and Australia regulate theirs — it's because it is. DSHEA was spearheaded by Orrin Hatch, the longtime Republican Senator for Utah who — you can guess where this is going — counts a sizable portion of his donor base from the supplements industry as well as a son, Scott, who lobbies on behalf of it. Supplements are one of Utah's largest industries and it's said that "one in four dollars in the supplement market passes through the state."

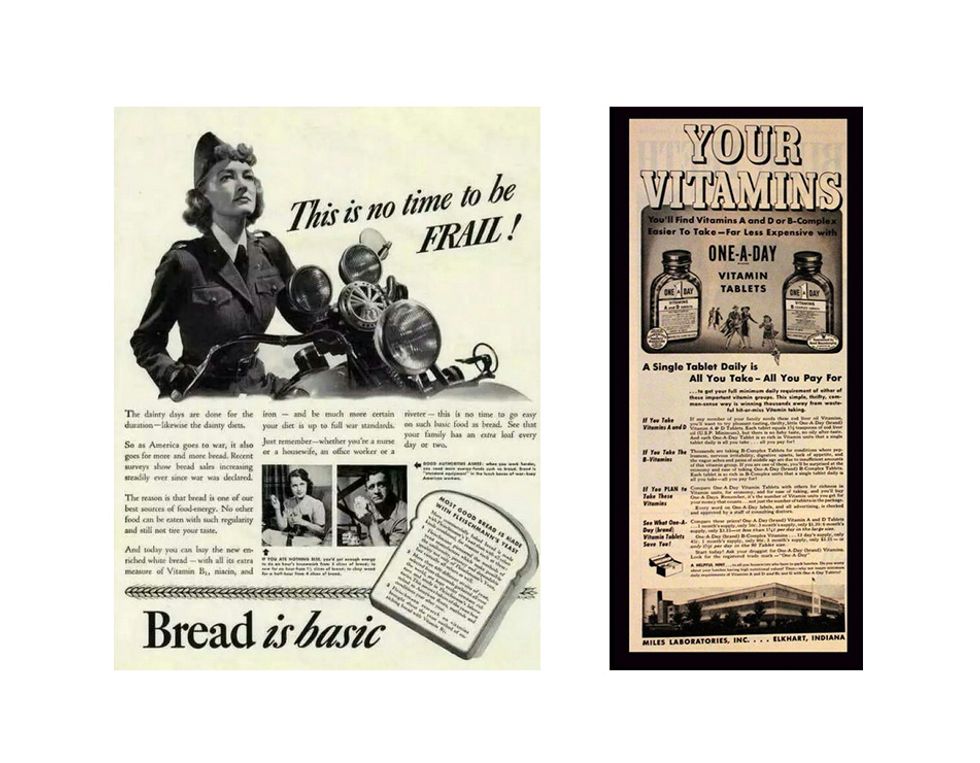

Orrin Hatch wasn't the first politician to give vitamins and supplements special concern. Franklin Roosevelt convened the National Nutrition Conference for Defense in 1941 in the lead-up to World War II, after hearing from military recruiters who were appalled at the malnutrition they encountered among potential soldiers (likely abetted by the deprivations of the Great Depression). Worried about sending weak troops into battle against vitamin-fortified Nazis, one of the key takeaways of FDR's conference was the importance of providing soldiers — and the population at large — with vitamins, via traditional pills as well as vitamin-enriched foods like flour.

Regular Americans continued to hop on the vitamins bandwagon and in the post-war decades, the industry's popularity dovetailed with '60s-era trends in health food and '80s-era trends in exercise and fitness. Along the way, each new iteration of health fad left its mark on the vitamin world, whether in the form of crunchy, Summer of Love-style packaging on multivitamin bottles we still see today or the sleek, '80s and '90s postmodern gym rat feel of health havens like GNC stores.

Today, vitamins and supplements branding continues to keep up with the times, thanks to the industry's ongoing freedom from medicine's packaging and design limitations. But this leeway comes with a challenge: broad competition.

As Alain Sylvain, founder and CEO of innovation and brand consultancy Sylvain Labs, puts it, vitamins and supplements aren't really battling against medicine for customers, but rather against anything that relates to "a healthy lifestyle and healthy eating" (think: kale, matcha, acai berries and things like that). You could even make the case that they're also competing with anything in the self-care realm that promises physical or mental well-being, whether that's an exercise class, meditation app or eco-friendly skincare products. It's this mix of design freedom and a wide variety of competitors, coupled with influence from larger branding and design trends, that has led to the emergence of revealing patterns in the ways that vitamins and supplements are marketed to all of us.

Among the most interesting patterns that have emerged are the subtle or not-so-subtle ways these new brands target a specific gender. Some of these brands (Ritual and goop Wellness) have language, either on their website or their packaging, that confirm their focus and target demographic is women (goop Wellness describes their products as "health-defining vitamin and supplement regimens that address the acute needs of modern women," for instance). Other brands (Care/of and Kion) aim to be more gender neutral and either eschew explicit references to men or women on their site and packaging altogether or include subtle cues like photos of both men and women on their webpages as a way to signal their broad appeal. Still others (Onnit, JYM, Old School Labs) likewise don't mention a target gender on their websites or packaging and, in some cases, explicitly make reference to male and female customers, yet the visual cues they offer are predominantly geared towards men (think a plurality of photos featuring men, a logo of a retro-looking hunk on a bottle or an 'About Us' page that lists a team comprised either mostly or entirely of men).

When asked about the thinking behind their logos and design, the brands we spoke to — even those that previously made it clear they were targeting one gender or the other — avoided making reference to any relationship between their packaging and gender cues. At Care/of, Co-Founder and CEO Craig Elbert emphasized "personalization" and a desire to create an experience that would be "delightfully simple on all levels." At goop Wellness, Ashley Lewis, the Senior Director of Wellness, said that they, too, "opted for meaningful simplicity" and that "the colors of each box are derived from the chakra relevant to each product's specific function." Kion was also inspired by eastern medicine traditions when it came to their branding. "What we wanted to get across was that marriage of ancestral wisdom and modern science," Kion's founder Ben Greenfield said, adding, "We wanted something kind of sharp, edgy, bold and fierce" that also referenced things like "life force, prana and energy." For its part, Ritual shared Kion's desire to signal a connection between left brain and right brain thinking. Their logos and packaging were meant to reflect an "intersection of science, art and technology," explained Ritual Founder and CEO Katerina Schneider.

Whatever each brand's intentions may have been, several outside graphic designers and branding experts we spoke to said they definitely picked up on gender cues in the logos and packaging. Looking at goop Wellness, Ritual and Care/of, David Gardner, the Founder & CEO of Chicago-based brand strategy and design consultancy ColorJar, says he'd assume these brands were targeting an "upscale female" demographic. "Each of these brands are cut from the same cloth of modern, clean design target[ed] at female shoppers," he says. "Their use of soft colors, ample white space, and elegant typography convey the thought and care behind the products." Katie Sadow, a designer at Sylvain Labs agrees. Focusing solely on Ritual and Care/of, she says that "with generously curvaceous wordmarks and subtle aesthetic nods to the cosmetic industry (especially in their digital presence), I'd assume that these brands were targeting a primarily female audience." In contrast, Sadow stated that with "wide and beefy wordmarks set against black backgrounds [that] speak of intensity, power, and strength," she'd assume brands like Onnit, JYM and InfoWars "are primarily targeting men." Dan Capuli, the Executive Design Director at Chicago-based creative agency Love + The Machine applauds the "daring" design approach of a brand like Old School Labs and its ability to "marry nostalgia and pop culture" while also being quick to discern that the brand "is clearly addressing the male-focused supplement market" with "a celebration of Mr. Universe-style machismo."

Several of these designers also noticed a seeming correlation between the presumed gender being targeted and whether the brands mirrored current design trends. Many spoke about a relationship between the "female-oriented brands" and design tropes popular among other new Millennial-focused brands. "If Casper mattresses made a vitamin, it'd look and talk like Ritual," Gardner said. Similarly, Sadow related that brands like Ritual and Care/of "would look comfortably at home alongside other direct-to-consumer hero brands of the moment like Everlane, Casper, Glossier, Hubble, Curology, Goby, Capsule."

Conversely, both Sadow and Gardner felt a lot of the "male-oriented brands" like Onnit, JYM and even Kion were "swimming against the current of modern design trends," (Sadow) with "GNC-style logo[s] and packaging [meant] to convey professional-level supplements" (Gardner) and a focus on things like function, fuel and performance. And while it's easy to dismiss these brands as either uninterested in design world trends or unaware of them, it's also possible that it was a conscious choice to eschew contemporary branding tropes.

By avoiding packaging that looks too of-the-moment, they might also be insulating their brand from being perceived as overly "trendy," "buzzy" and, possibly by extension, "unserious." It's a tactic that might decrease interest from a broad base of curious vitamin and supplement neophytes but also appeal to a smaller, more engaged group of hardcore fitness buffs, bodybuilders or biohackers, demographics that are reflected in both the backgrounds of these brands' founders as well as their products, packaging and website information. (Onnit and JYM could not be reached for comment).

These connections between branding, gender and modernity also raise interesting questions about how the vitamins and supplements industry assumes that women and men think about health and wellness or, perhaps, should think about health and wellness. As Alain Sylvain sees it, the design of female-oriented brands like goop Wellness or Ritual appears "solution-oriented" while those of the more male-oriented brands like Onnit, JYM or Old School Labs appear "much more problem-oriented." Sylvain explains that the former type takes a problem the customer already has and wants to fix and offers a solution while the latter type "alert you to what you don't have" (or don't have enough of) and offer you a way to get it.

By "starting with a problem," these problem-oriented brands that are marketed towards men, seem to be saying "there's a crisis that you need to take a rational approach to correcting," Sylvain says, adding that it's "no coincidence" the packaging of many of these brands are "darker in tone." They're "tapping into a fear in people, whether that's a need to work out or take care of oneself. It's a kind of guilt," he says. But, there is an emotional benefit for the consumer when buying a brand like this: the "confidence" it promises to bestow. The emotional benefit that the female-targeted, solution-oriented brands provides, in contrast, is "peace of mind." These brands are more "optimistic" and are "about self-care versus fixing a problem." They're expressing a more "hopeful side" that reminds you of "self-pampering," Sylvain says.

Of course, while the gender stereotypes about "men being more rational" or "women being more emotional," don't apply to many people, there are certainly plenty of women who might be attracted to problem-oriented brands as well as men interested in those oriented around solutions. But still, even if you're not a design industry professional, it's easy to spot this division in the supplements market and the different cues each side consciously or subconsciously gives off. It also says a lot about society's overall stereotypes about men and women and our different views towards health, wellness, exercise and nutrition. There is, however, one recent development that might unexpectedly upend the industry, affect male and female customers equally, and cause these two camps to align not only their packaging but also their products: Orrin Hatch's upcoming retirement later this year.